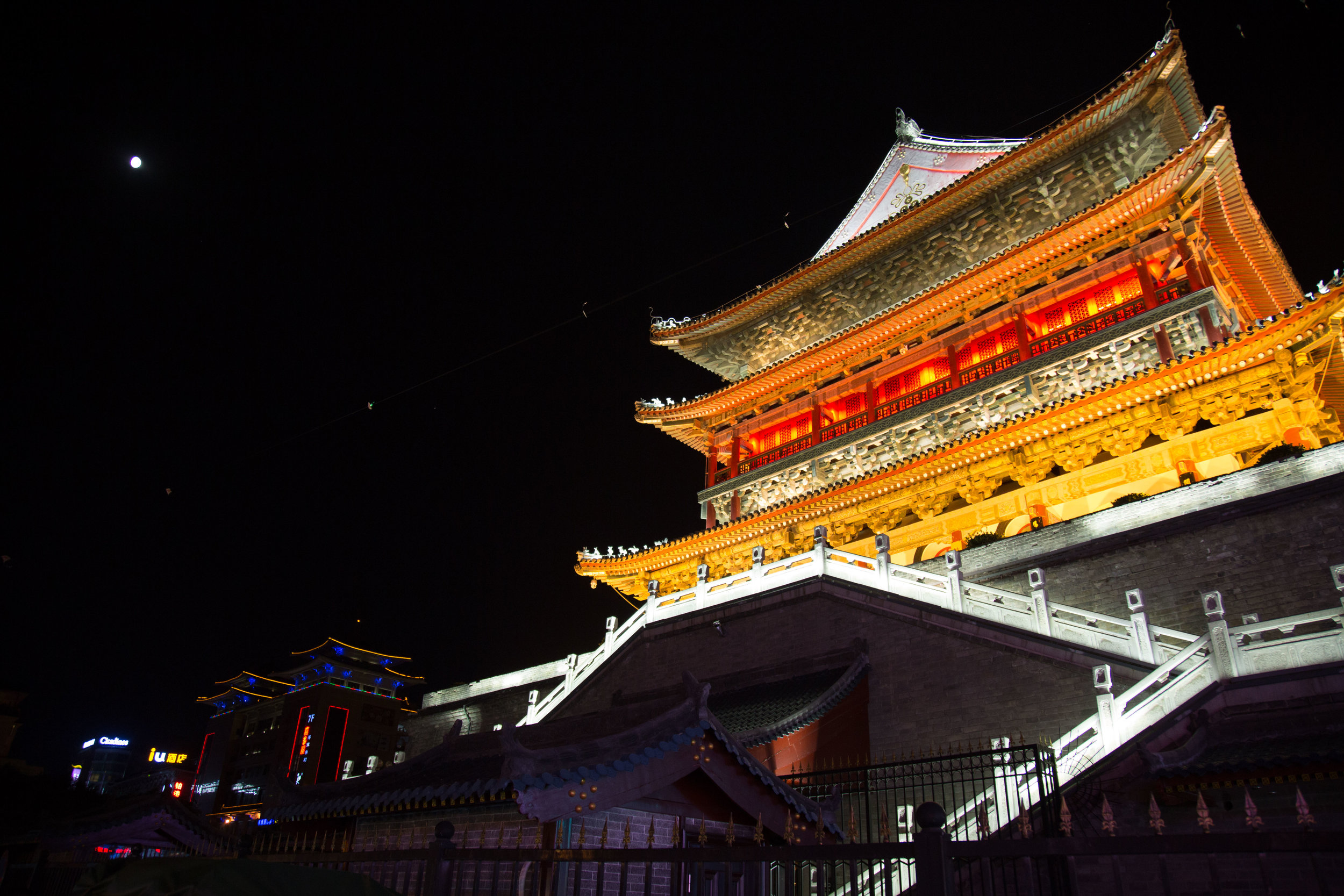

Yesterday, I visited a u.lab hub in Xi'an, China. The city is one of the "Four Great Ancient Capitals of China" and is also home of the Terracotta Warriors.

The hub in Xi'an has 500 members. A smaller subset is currently meeting monthly, for nine months, to take a deep dive through the U process using the u.lab Massive Open Online Course as a guide. Each meeting involves a two day immersion during which the group completes a week of the course together. This week is their fifth meeting in 2016, and when I arrived they were reviewing the videos from Week 4 and just beginning to watch videos from Week 5.

Origins

The origins of the Xi'an hub date back to February 20, 2015, when Hui Zhang presented a case during a u.lab coaching circle.

A coaching circle is a group of 5-6 u.lab participants who meet weekly to apply Theory U to a leadership challenge one of them is currently facing. Members take turn presenting a case and that week Hui Zhang's opportunity had come.

She explained her intention: she wanted to create a new type of book club where people do more than just read together. She envisioned a platform outside the traditional workplace for people to form connections, apply new practices, and have deeper conversations. Although her intention was clear, she was struggling to identify how to move into action.

The following day, a member of the coaching circle reached out and encouraged her to quickly write a business plan. She did, and two weeks later the club held its first activity. Word spread quickly around Xi'an. In its first year, the club hosted more than 50 offline activities, completed five books, attracted a membership of more than 500 people in Xi'an who stay connected through WeChat, and engaged a smaller core group of about 40 people who meet for the offline activities.

At the beginning, Hui Zhang struggled keep pace with demand. She was still figuring out the business model and didn't know where money would come from. "I realized you just have to keep walking," she said, "and the resources will eventually show up. Today, people no longer talk about it as her club, but as our club. "I'm just one of the people now. It's not about me. I'm just here to serve whatever is needed."

In March 2016, Hui Zhang decided to facilitate the u.lab experience for members of the club who, like her, were interested in developing new business models for their own initiatives. Twelve people joined. Below are a few observations I wrote down during my visit explaining how they operate when they meet to take u.lab together.

Space

There was nothing remarkable about the space itself. A room on a top floor of a local office. A dozen chairs, a projector, speakers, and a few light snacks. It could have been taking place anywhere (which is exactly the point of a u.lab hub). The small air conditioning unit was no match for the stifling heat and humidity outside. So rather than natural light and a view of the city, which is normally ideal, we settled instead for the relative cool offered by a black-out curtain. In this case, the curtain was a good choice.

Business Model

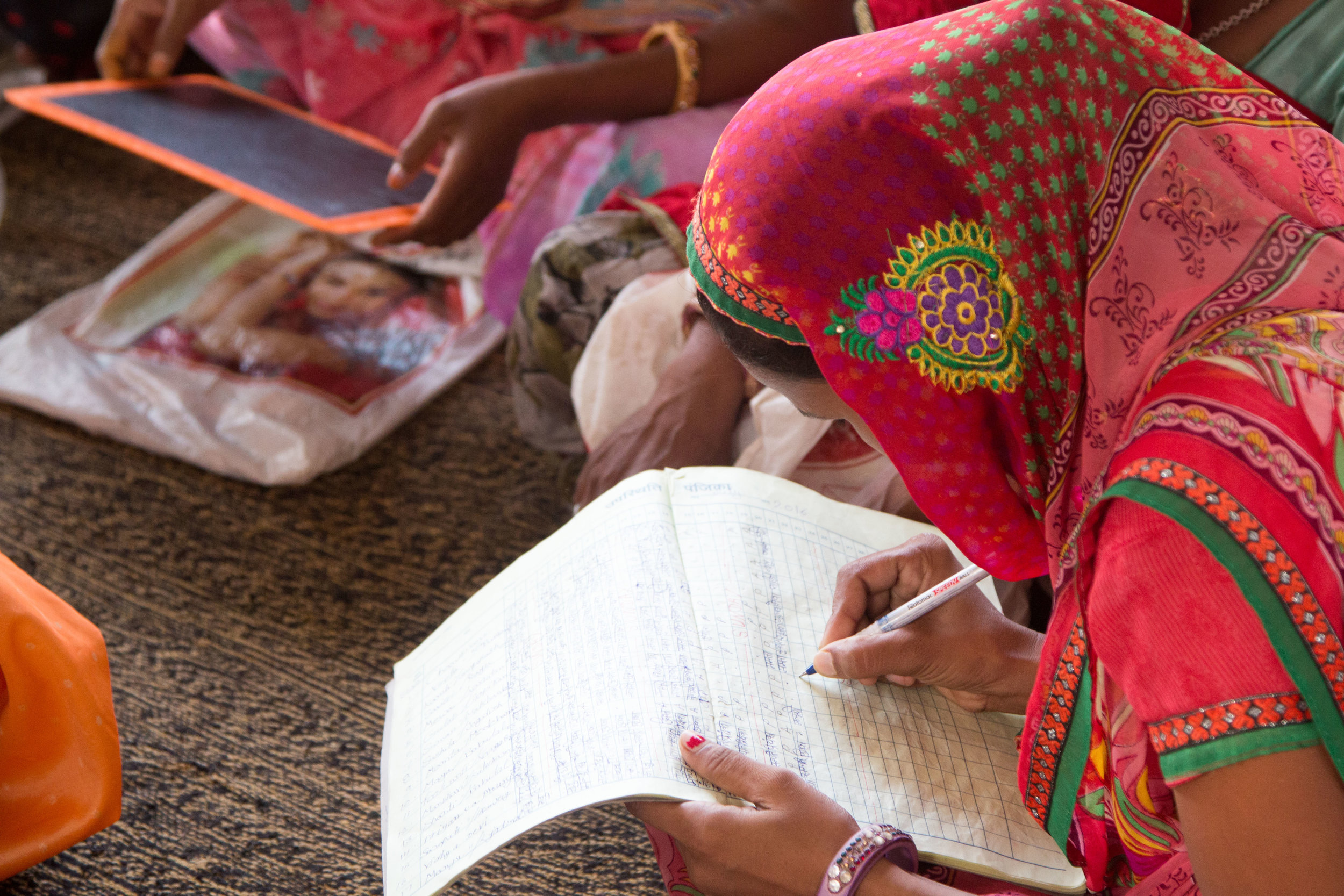

Looking around the room, I noticed everyone had a printed blue booklet with the transcripts for the week's videos (all translated into Chinese). Later on, when Hui Zhang was telling me the story of how she created this hub, she mentioned the printing and its associated costs. I asked where she got the money, at which point she gave me an overview of the hub's business model.

To join, a participant pays 3,000 RMB (about $450 US dollars). Some of the fees cover her direct costs. A percentage is given to a local children's charity. In addition, by joining the hub, participants must commit to developing and prototyping a business model during the course that will generate 3000 RMB in revenue - effectively meaning the hub experience pays for itself.

Hosting Process

The group had met the night before for a dialogue session, and it was clear that many of them were still moved by the experience. I had planned to join them Saturday night, but upon landing in Xi'an, I learned their 17th floor apartment had lost power and the elevator wasn't working. They suggested I meet them the following morning, and looking down at my oversized luggage and camera bag, I agreed that would be best.

The Sunday morning session was scheduled to last from 9am-noon. Because I was visiting, each person took a few moments at the beginning to introduce him or herself. There were ten women and two men. One was an HR professional, another IT manager, a mechanical engineer; one of the men was a radio show host. A young woman owned a local coffee shop. After each person had a chance to check-in, Hui Zhang and her co-host introduced the theme of Week 5. Hui Zhang had the week's videos pre-loaded onto her computer. Rather than clicking through each page of the course on XuetangX (the Chinese partner of edX) they had a far simpler process:

- Project a video onto the wall

- After the video, form groups of 2-3 and share what stood out, surprised, or inspired you

- Return to the larger group to share key insights

They started with a guided meditation practice from Week 4, which was filmed at Walden Pond, just outside of Boston. They also watched a video on presencing and absencing, the TED talk by Brene Brown, and few videos that introduce the principles and practices of crystallizing.

In some instances, one of the facilitators would offer opening or concluding remarks to put the main concepts of the video into a local context. For example, discussing the shift from presencing to crystallizing, one of the facilitators emphasized the importance of staying connected to the "big Me" (who is my Self/ what should I do) and the "big It" (what is my Work/ what does the bigger field want me to do). "This means we need to learn to see what China needs us to do," he said, "and what Xi'an needs us to do, rather than just paying attention to our own individual needs." He summarized by saying, with a big smile, that we should aspire to "use the big Me to do the big It!"

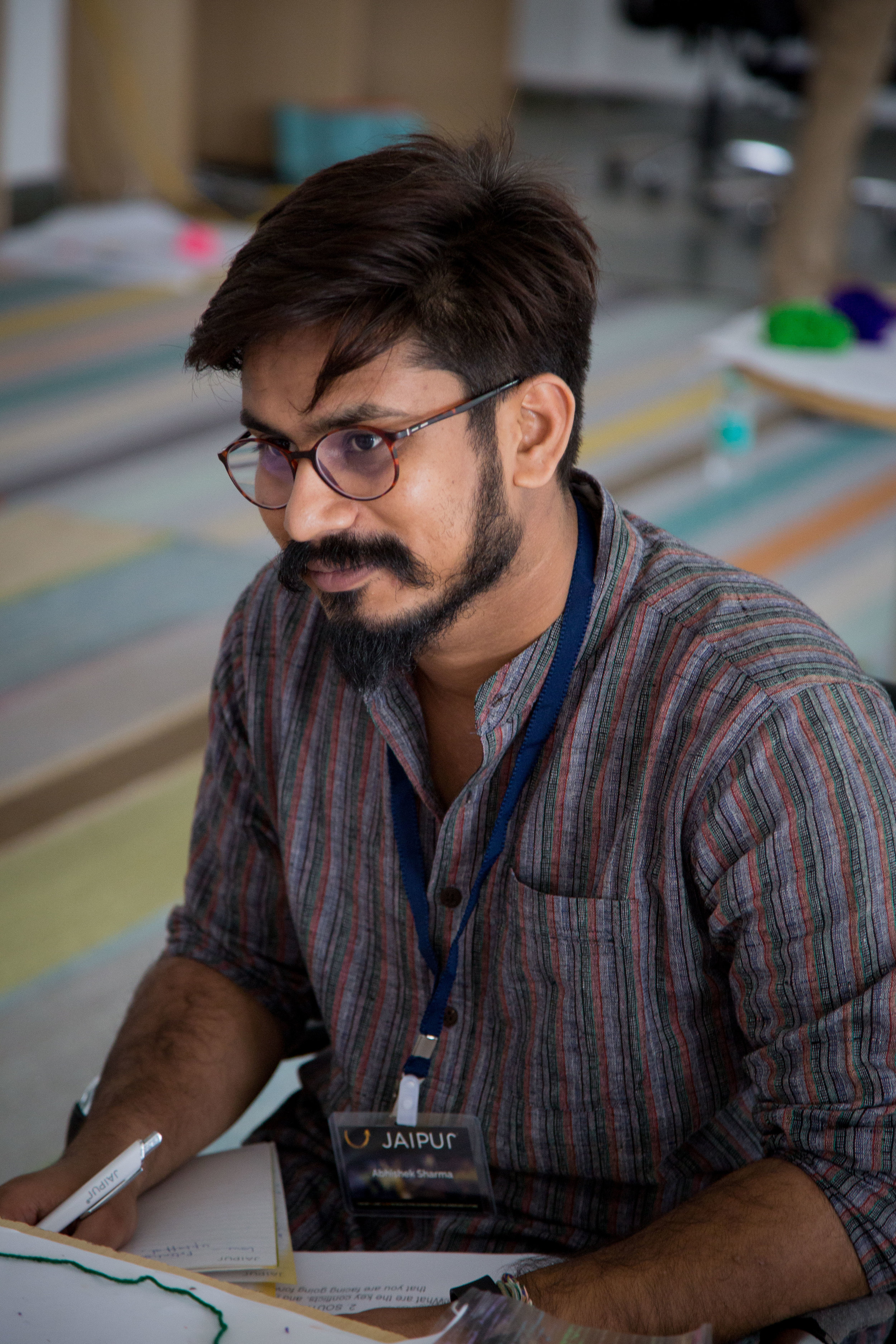

Watching them interact with the material and each other drove home for me how important good quality hosting is to the hub experience. A good host doesn't have a personal agenda. He or she mainly holds space for others. A good host also helps bring the course material down to earth by helping put the ideas we present in the videos into language and a context that makes sense locally.

Why take u.lab together?

From my short time with the Xi'an hub, at least three compelling reasons stood out for taking the course together. Those were:

- Relationships

- Accountability for action

- Engagement

Through the quality of conversation they had in small groups and the bigger circle, I could see these people really valued the relationships they had formed with each other. This was underscored during the check-in when one participant said: "During the time we have been doing this workshop [u.lab] together, I've felt that we are each streams flowing into a river. We've learned to trust each other."

There is also a deeper accountability for moving into action. Even though the hub is only five weeks into u.lab, three new organizations are already emerging from this twelve-person group: the Shaanxi Province Non-Violent Communication Community, The Institute for Questions, and another iteration on the reading club.

Finally, engagement: as the main producer of the u.lab videos, I've watched them all countless times. And yet, sitting amongst a group of people who were intently watching, I also found myself paying attention to the content in new ways. Perhaps it's similar to practicing a sport, yoga, or meditation with others rather than alone: you're pulled into a different space by the collective attention that others are simultaneously applying to the task at hand.